Future of work – Labour market evolutions post pandemic and the employment contract

by Etienne Pretorius

In many countries globally generational advancement is coming to a complete stop. When housing costs are taken into account, those in their 20s and 30s today have incomes that are no better than those in the prior generation at the same age. With the salary gap between older and younger workers continually increasing the future is uncertain. Young people desire occupations and organisations that are well suited to their abilities and values, as well as those where they can collaborate with others who share those values. They are ready to switch careers if necessary and with the proper support.

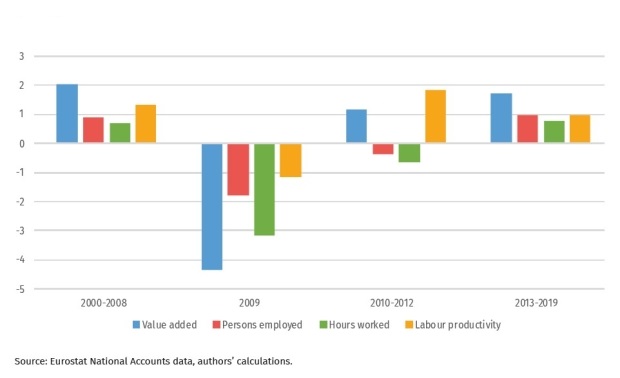

WIIW reports that the pandemic’s economic impact has sent the world economy into a recession. Well the western economies at least, since China even demonstrated positive growth in 2020 as a result of a robust economic rebound that began in the second half of that year. The reason for the sluggish recovery of hours worked after the hit of the financial crisis in 2009 was a low growth rate of economic activity in 2010-2012 with around 1%, accompanied by a high growth rate of labour productivity of around 2%, and a slightly lower average growth rate of economic activity from 2013-2019 as compared to the pre-crisis period 2000-2008 with labour productivity growth being at around 1%. The growth rates for the different time horizon are presented in the adjacent figure.

Overall, this shows that following an economic shock, the development of (labour) productivity growth and the recovery of employment or hours worked levels, or the labour market in general, heavily depend on the macroeconomic environment and current macroeconomic policy actions. Additionally, even if the economy is rebounding swiftly, one should not automatically anticipate a quick return of employment and hours worked levels, which also depend on the dynamics of productivity and labour supply.

After comparing the COVID-19 crises’ effects on employment to those of the global financial crisis in 2009 and examining long-term growth rates, the most crucial question is how labour demand will change over the coming years and when employment levels from before the crisis will be restored. This impacts the conversation about redesign of the employment contract as expectations between employer and employee shift to meet new era objectives.

The International Labour Organization reports that a corresponding emphasis on emergency income support arose over the past two years, even if periods of job retention remained through 2020 and 2021 and have not yet fully ended (2022). Whatever the case, a situation of pervasive (relative or absolute) poverty was brought about by the existence of sizable populations of employees and people without adequate social insurance coverage. When this pressing issue surfaced in the second quarter of 2020, many nations responded to it in various ways. The nations either provided targeted grants to groups of workers who were not covered by social insurance or formalized minimum income as assistance programmes so as to offer a floor on income as a “automatic stabiliser.” Most importantly for the Global South, active labour market policies were employed as a way to boost income, particularly through public works or training initiatives that catered to uninsured workers without immediate financial sources. The need for more targeted policies to support those at risk of getting stuck in the challenging transition from education to work, such as young labour market entrants, and those who lost their jobs and income and needed some assistance to find new employment opportunities also emerged during the early phase of the pandemic, even though these two clusters of measures—job retention policies and emergency income support—were primarily implemented during that time. It is encouraging to observe that the most recent policy experiences in reaction to the COVID-19 crisis have already produced some promising results that may theoretically be included into a post-pandemic framework for labour market strategies.

In terms of the employment contract there is a diversity of conversations taking place. The WEF Davos meeting in May 2022: Jobs and skills covered many of the pertinent topics.

- Accelerating the reskilling revolution

- Revaluing essential work

- Creating a global skills framework

- The global workforce: empowered but divided

- Where will the jobs of tomorrow come from?

- Hybrid work: What happens next?

- The future of work learning

- Responding to the Great Resignation

- Wages in the spotlight

- The four-day week: Necessity or luxury?

- The future of the Gig Economy

- Integrating refugees into labour markets

- The global jobs outlook

With labour markets in flux from the fallout of the pandemic, technological shifts and the green transition, up to 1 billion people will need reskilling, training and lifelong learning by 2030.

WEF World Economic Forum Davos May 2022: Jabs and skills

Considerations and debate regarding the future of work is having a heavy impact on relationships between employer and employee. Both parties are having to become dynamic in the debate. Significant compromises are being made on both sides of the table as people are reconsidering priorities and expectations of one another. One thing is certain, that things will not be the same again.

The post-pandemic reluctance of employees to return to the office has been well recorded. This hesitation ranges from the phenomena of “silent resigning” to the huge resignation. Other changes are occurring as a result of the subsequent economic slowdown: job offers have been withdrawn amid layoffs in technology firms that are frequently regarded as growth engines, and a STEM skills shortage has prompted calls for workplace upskilling and re-skilling programmes and a global competition for talent. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, did not cause many of the patterns we are today observing in the workplace. Here are five shifts that appear to be here to stay:

- Restructuring companies for efficiency

- A shift to skills-based hiring

- The mobility of talent

- The rise of ‘work’ and the decline of ’employment’

- The central importance of digital skills

Acknowledgement

- Authored by Stefan Jestl and Robert Stehrer (4 August 2021) The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Wiener Institut fur Internationale Wirtschaftsvergleiche (WIIW), (Post-)Pandemic Employment Dynamics in a comparative perspective [Accessed 27 October 2022]

- Authored by Werner Eichhorst, IZA and University of Bremen, Paul Marx, University of Duisburg-Essen and IZA, Ulf Rinne, IZA, and Johannes Brunner, IZA. (June 2022) International Labour Organization, Policy sequences during and after COVID-19 [Accessed 27 october 2022]

- WEF World Economic Forum Davos May 2022: Jobs and skills [Accessed on 23 May 2022]

- Authored by Segun Ogunwale (9 September 2022) WEF Five key trends shaping the new world of work [Accessed 27 October 2022]